Land and Waters

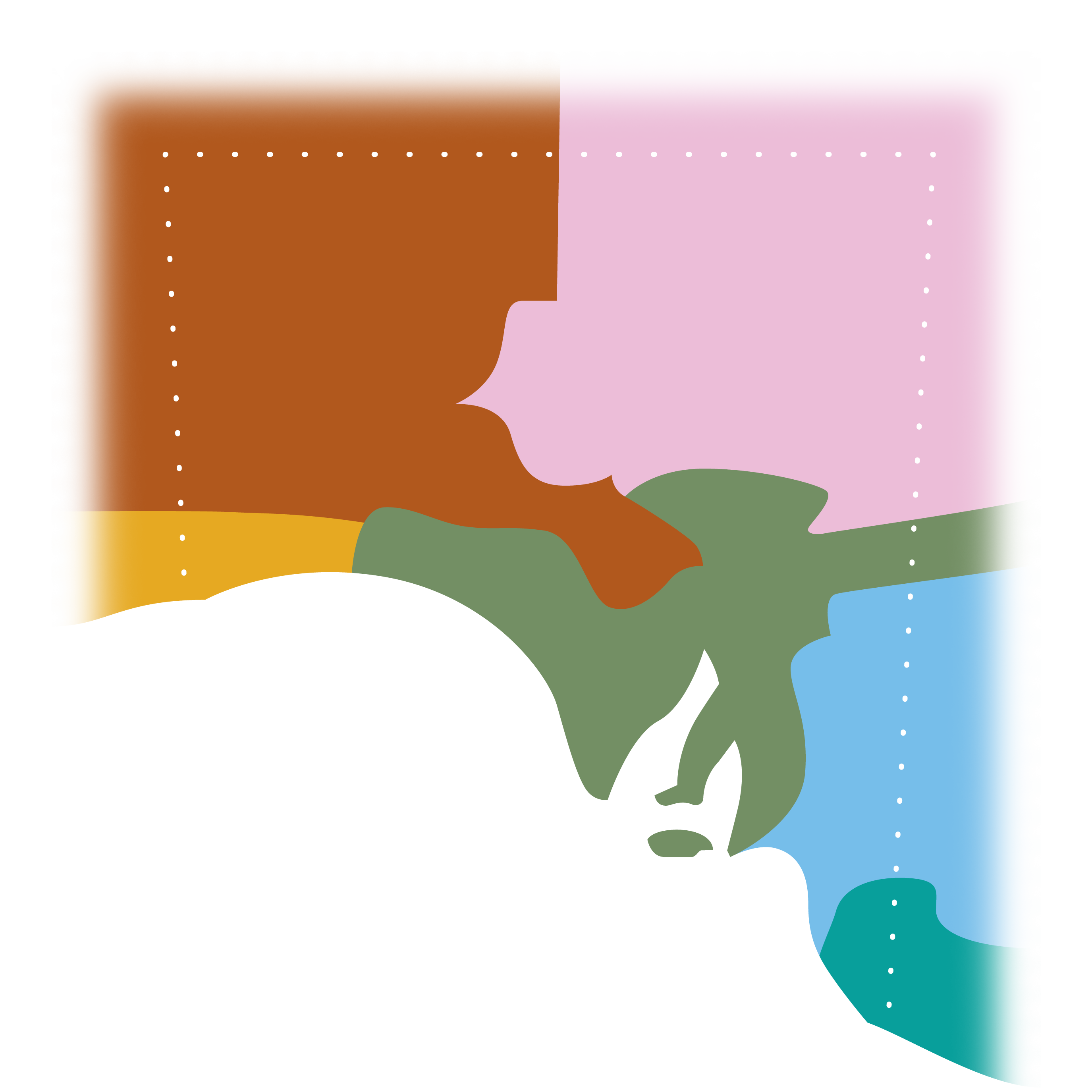

Tanganekald names for our country.

Ancestral Beings and their adventures show Tanganekald people how to understand the world and our place in it. Tanganekald placenames, songs, and stories record ancient events that have contributed to the shape of the land and the world around us. These uses of language provide guidance on how to divide the land and waters of the Coorong into zones, as shown by the names in the mud map above.

Sean Weetra near Raukkan. Image © Ben Searcy 2021

Sean Weetra talks about some his favourite plants and places of the Coorong.

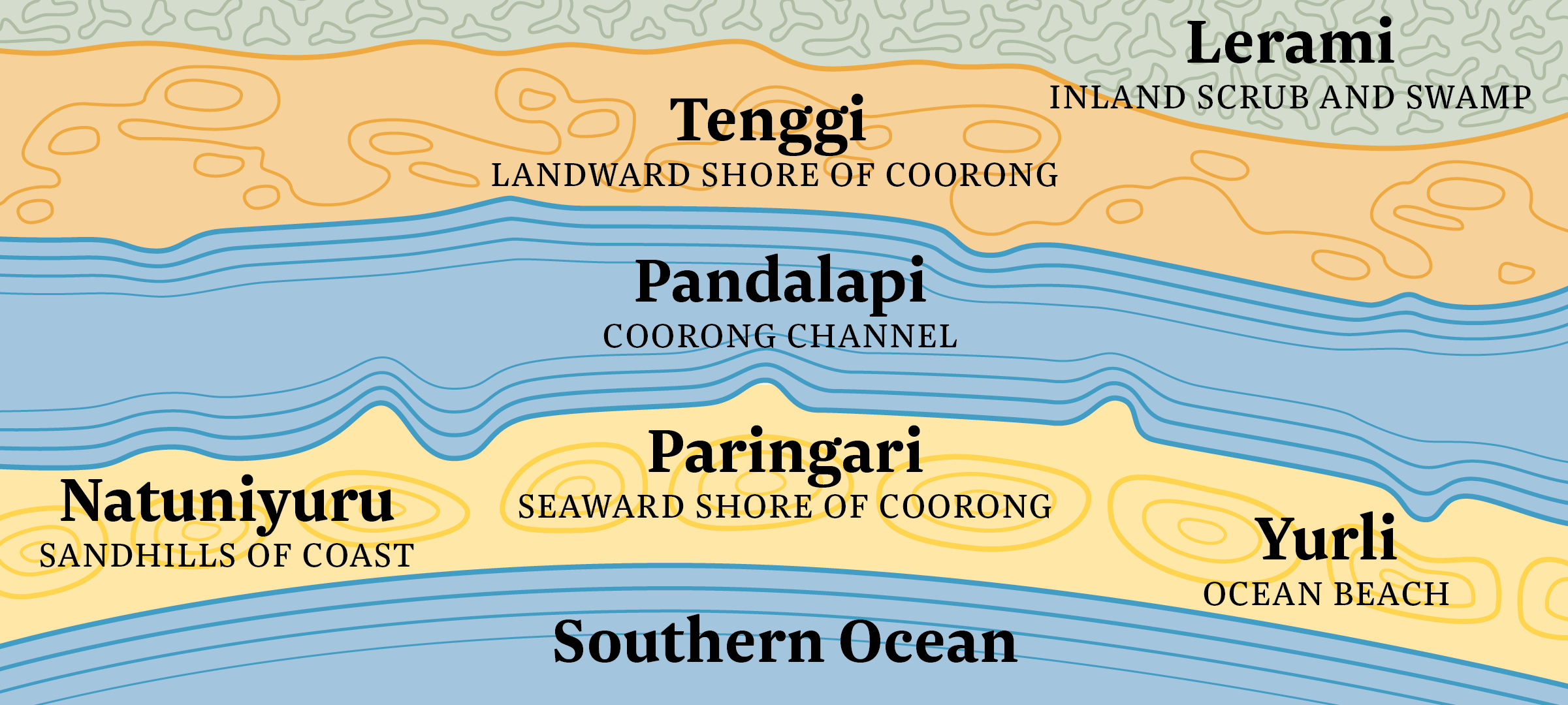

The lerami is the scrub and swamp zone inland from the Coorong channel. Traditional Tanganekald people moved camp to the lerami in the colder months to escape the strong ocean winds. At the lerami our ancestors built shelters consisting of a wooden frame covered with reeds. They faced their shelters away from the direction of the prevailing wind and built a fire in the opening. Other materials such as hessian and blankets were used as they became available and as traditional materials became scarce. The scrub provided opportunities for hunting small and large game with nets, spears, clubs and boomerangs. Animals provided food and raw materials for clothing and other implements for daily living. Sinew from kangaroo tails was used for binding spearheads and bones were used to make weapons and needles. Swamps provided a rich habitat for fish, ducks and other migratory birds. They were also a source of plants used for food, medicine, and the making of everyday tools and utensils such as baskets.

Camp near Raukkan, 1880. Camps made using traditional materials tended to be much more structured than this.

AA 492/1/3 Samuel Sweet collection South Australian Museum Archives

Milerum breaking an emu leg bone to make a tool for basket weaving, 1937.

AA 338 Blue Folder 3 Norman Barnett Tindale collection South Australian Museum Archives

Robert Wuldi on making a mathuwi mayinggar (Boss cloak), and reviving the art of making possum skin cloaks. The lerami was a traditional possum habitation. The illustrations on the cloak document the recorded history of the state.

If you journey by road to the Coorong today, you will travel on the tenggi. The Princes Highway was used as a route to Victoria and the gold fields in the early days of the colony. Tanganekald people also travelled across the Coorong channel from the tenggi to the paringari (seaward shore). Tanganekald people developed an understanding of the best places to cross from the tenggi as the water level in the channel ebbed and flowed. This knowledge provided access to favoured camping places and a rich abundance of water-based resources.

Camp on the tenggi, 1844.

AA 8/2/12/1 George French Angas collection South Australian Museum Archives

Before barrages were built in the lakes system, water seasonally washed down the Coorong channel from the River Murray. Before the massive ecological disruptions of the colonial era, the brackish waters of the Coorong were rich in plant and animal life. This abundance afforded one of the highest population densities of Aboriginal people on the Australian continent prior to colonisation. The Coorong channel was crossed in places by foot or by ngalayi (raft). Ngalayi were made by bundling up dry grass-tree flower stems. A number of these bundles were lashed together to form a rectangular raft, which could then be poled across the lagoon. Nganangkuri (fish trap walls) were built along the Coorong for capturing schools of fish. These walls can still be seen today on the tenggi side of the lagoon. As early as 1934, Milerum expressed deep concern about the changes to the Coorong ecology wrought by commercial ventures such as fishing and farming. 'Nowadays, fishermen put nets across the Coorong in the narrow channels and catch all the mulloway before they spawn.' Milerum 1934 Today Tanganekald are working in partnership with the Ngarrindjeri Aboriginal Corporation and the SA government to rebuild the ecology of the Coorong and surrounding areas.

Pandalapi – Coorong channel. Image © Ben Searcy 2021

Listen to Betty Sumner’s brilliant telling of the Mulyawongk story. Mulyawongk is a mysterious water-living creature who eats children if they wander near water after dark. The story is shared widely with other groups in the Riverine region.

The Paringari was a favourite camping place. It provided access to the resources of the pandalapi and to the yurli (sea coast). It was well protected from the prevailing winds and was relatively secure from attack by strangers. According to Milerum the natuniyuru (coastal sandhills) provided many excellent lookout points, providing a clear view of anyone approaching from the landward direction.

Paringari (top right). Image © Ben Searcy 2021

The natuniyuru is a continuous line of sandhills separating the paringari (seaward shore of Coorong channel) from the yurli (ocean beach). The sandhills served as important lookout points. They also provide important habitats and protection for a number of plant and animals species, including small reptiles and nesting birds. Milgi (pigface) is a common plant found here. The fruit can be eaten, the leaves are a portable source of water, and the dried milgi can be mashed into a type of cake.

Natinyuru (background). Image © Ben Searcy 2021

The ocean beach of the Coorong region is known to us as the yurli. In Tanganekald we call the Southern Ocean yaluwar. Cockles, an abundant food source, were collected on the yurli and carried back to the camps in woven baskets. Shell middens mark these camps, testifying to our long connection to country. The seasons and tides would tell us when it was a good time to go fishing or gather cockles. The old men knew when to fish or gather cockles by listening to the roaring of the ocean. Tanganekald people are not whale hunters but we ate them when they were washed up on the yurli. This usually happened in the colder months and led to great feasting of whale meat. Other parts of the whale were used too, such as the blubber, which would be rubbed into the skin to protect against the cold.

Yaluwar (Southern Ocean). Image © Ben Searcy 2021

Ted Gibson gathering cockles on the yurli.

AA 263/5/page 148/3 William Ramsay Smith Collection South Australian Museum Archives