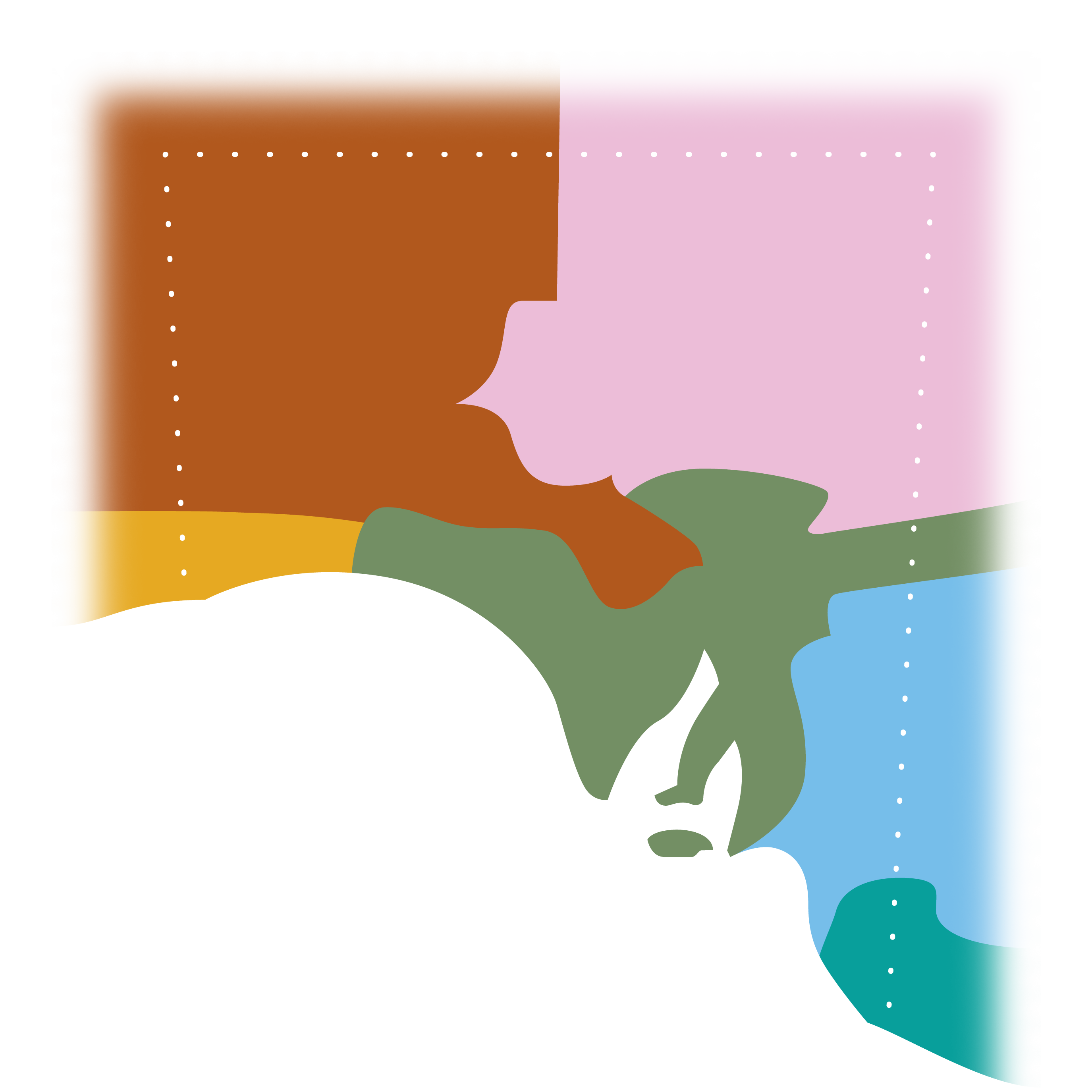

Weaving

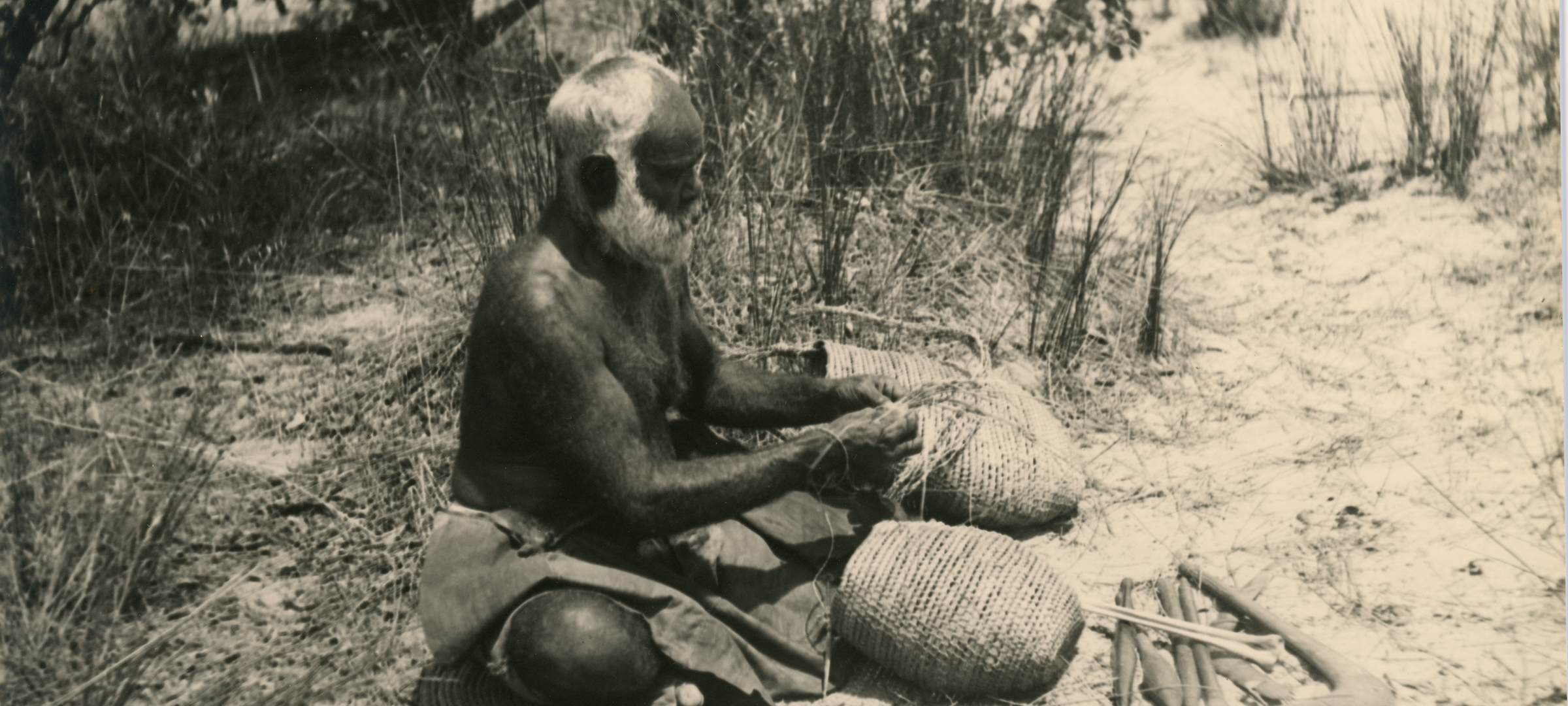

Milerum demonstrating traditional weaving practices, ca 1937. AA 338 World of Milerum Photos & Slides Norman Barnett Tindale Collection South Australian Museum Archives.

Lakun

Lakun means 'to weave something'. Weaving as an activity and as an idea remains strong in contemporary Tanganekald lives. While weaving was traditionally an art practised by women, Milerum demonstrated how to gather grasses and produce beautiful mats and baskets, many of which are stored at the South Australian Museum. Milerum realised the importance of making a record of these skills and knowledge relating to them. Weaving maintains an important role in Tanganekald culture. Here we present some examples of our weaving practices. These include those of great-grandfather Milerum and contemporary practitioners, including Auntie Betty Sumner and artist Robert Wuldi. Robert Wuldi takes up the idea of weaving in his art practice. If settler-colonialism has taken away many of the raw materials for producing woven artefacts - why not use the materials of the settler economy? Watch the video below to see this fascinating transformation of the idea and practice of weaving.

Listen to Betty Sumner and Robert Wuldi talk about their weaving practice.

'It made me more relaxed, made me think more about my ancestry, about my people. So that all goes through your mind. It's just the one stitch that we use ... you can use your imagination to go all kinds of ways.' Betty Sumner 'I see his [Milerum's] weaving and I do think that I'm following in the same vein.' Robert Wuldi

Like learning a language, our journey starts with one stitch. Beginning the process is the biggest step with endless possibilities.

There are many different types of grasses used in traditional weaving. This includes sedges, which grow around the edges of lakes and other fresh water areas. Many of these species of grasses are disappearing from the Coorong region owing to agricultural practices, and the weaving community are helping to bring this issue to light. One thing we are doing is harvesting the grasses - this helps them to grow back stronger. The grasses are gathered by hand, dried in the sun and then stored until they can be turned into a woven piece. Last century, many woven pieces were produced for sale to tourists and museums. This extended the traditional use of weaving into the cash economy. Tanganekald have continued to apply our ancient weaving practices in new ways, including to the creation of fine art objects which are coveted by major galleries both locally and abroad. Twenty-first century artist and great-grandson of Milerum Robert Wuldi uses galvanised and copper wire in his weaving practice to challenge settler-colonial interventions which prevented his ancestors from accessing grasses and their land. Clearing, stocking and fencing land with galvanised wire damaged and made inaccessible raw materials for weaving. Norman Tindale of the South Australian Museum, working with Milerum in the 1930s, observed the drastic changes to the riverine ecology brought about by the construction of barrages. Robert's use of copper wire salvaged from abandoned white goods also makes an ecologically-minded statement about waste. Ngarrindjeri weaving styles have been adopted by other Aboriginal groups and Indigenous art centres around the country to reinvigorate cultural practices. Today, many weavers run workshops for the wider Australian community to learn about this culturally significant art form.

Grasses on the Coorong. Image © Ben Searcy 2021

Tanganekald people traditionally wove many different objects including nets, mats and a variety of baskets. The design of baskets varies depending on their use, for example, baskets to carry cockles are of different shape and size to baskets for carrying weapons.Both men and women were involved in weaving to create pieces which suited their particular needs. Woven baskets may have been decorated with the addition of feathers. If the feathers used were derived from the maker's ngaitji (totem), this increased the power of the object and were particularly used with war baskets.

Betty Sumner weaves using the traditional looping stitch.

Robert Wuldi weaving with galvanised wire, which represents the fences that prevented Tanganekald people from accessing their land. Image © Ben Searcy 2021

Follow the link below to learn some words for the different types of woven pieces and tools.